On the occasion of the death of ‘The Iron Man’ – Mick Murphy – I am making available this chapter from my book The Rás: The Story of Ireland’s Unique Bike Race (Collins Press 2003).

Some background to this story, along with a reflection on the wider character that was Mick Murphy, is also available here ….

Chapter 6: The Iron Man

Banteer is a small village, west of Mallow in County Cork, where the rich farmland of the Blackwater Valley meets the Boggeragh Mountains. Two miles from the village, where the road to Cork city begins to rise for Nadd mountain, lies the crumbling and ivy-covered remains of a ball-alley at the side of the road. Here, in the rural and parochial Ireland of the 1950s, the local men gathered in the summer evenings when the day’s farm-work was done. Life didn’t change much in rural Ireland in those times and anything out of the ordinary was a source of local interest and speculation. In the spring of 1958, the curiosity of this gathering was aroused by the regular appearance of an unknown cyclist, head down, and heading south towards Nadd mountain. While his unfamiliarity was of interest in itself, the fact that he didn’t return intensified the curiosity. Some, it is said, remained later and later, until well into the dark of the night, but still, he was never seen returning.

The mystery rider was Mick Murphy, a 24 year-old migrant farm labourer from an impoverished farming community near Cahirciveen in south Kerry. He was unknown to the locals as he had come to Banteer to prepare for the 1958 Rás Tailteann, and his regular evening spin past the ball-alley took him over the mountain and back to Banteer, via Mallow, on a 50-mile (80 Km) circular route. However, within a few weeks, local curiosity was to be satisfied when Murphy become a national sporting sensation by emerging from nowhere to win the 1958 Rás in such spectacular fashion that it created one of the most enigmatic legends in Irish sporting history.

Legends abound about Murphy, both of his feats on the bike and of his eccentricities, and his path to the 1958 Rás is as extraordinary as his winning of the event itself. The reading of some of the contemporary newspaper accounts of the race raise a niggling doubt about their accuracy and bring to mind the saying that “the truth should never spoil a good story.” The superlative headlines of the Kerryman newspaper described Murphy as a “sensation”, “mile-a-minute Murphy” and “fabulous”. Its stories described a hitherto unknown cyclist romping away from the bunch, seemingly at will. They outlined how, punctured and unsupported at the side of the road, he grabbed a common bicycle from a spectator, chased and caught the bunch. They described almost daily crashes that left Murphy bruised and bloodied, needing hospital treatment at the end of a stage and being strapped to his bike the following morning. They tell of the “great Gene Mangan”, giving his bike to Murphy after a crash and thus forfeiting his own Rás chances. And, after all this, Murphy was still able to ride away from the bunch on the very last day, ride in front for over 100 miles (160 Km), and eventually win the Rás by almost five minutes!

Even if the Kerryman reports might be excused for having been slightly partisan, the extraordinary nature of Murphy’s win is verified elsewhere – the Cork Examiner reports referred to a “a truly magnificent performance”, the Irish Independent described Murphy as “incredibly durable” and the more constrained and measured language of the Irish Times even rose to such adjectives as “remarkable” and “fantastic”.

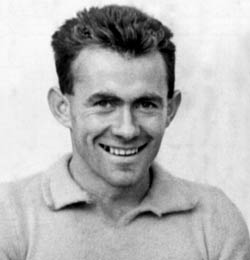

Mick Murphy was described as ‘barrel-chested’ and had laughing, mischievous eyes – “he was small, sturdy and desperate strong – he could pedal from morning ’til night”

Mick Murphy was born in 1934 into a small hill-farm, near Cahirciveen in County Kerry, that supported seven cows, an acre of potatoes and an acre of oats. His mentality was to be greatly shaped by the austerity and frugality of the physical, economic and social environment of his youth. On what he described as the “mean and bad” land of the region, it was common for young children to contribute to the labour-intensive farm-work and he got little schooling. At the age of twelve he was adding £3 (€3.81) per week to the farm income by drawing turf from the bogs with a donkey and creel during the ‘Emergency’ of the Second World War. He was taught to read and write by his mother and developed, through reading, an interest in the world outside of Cahirciveen – a trait that was to be central to his eventual athletic success.

Murphy’s introduction to athleticism came through a neighbouring farmer, Joe Burke, who was interested in circus acting and performed in the various touring circuses that regularly visited the locality. Murphy became Burke’s assistant and apprentice, and one of his earliest memories, on the day before his first Holy Communion, is of a row that developed when his mother stumbled across Burke practising one of his tricks – she beheld Burke walking around his farm-yard, with a ladder balanced on his chin, and the young Murphy tied to the top of it.

At the age of twelve, Murphy was initiated by Burke into the circus world – a realm of professional performers who were part of a network that stretched across Europe. They introduced Murphy to sophisticated training techniques, weight training and an awareness of diet. The circus people also gave have him access to literature on training which he studied intently. He built up a gym and training-circuit at home and began a life-long interest in weight training.

One of Murphy’s first competitive interest and success was in running. There was an abundance of sports and flapper meetings in Kerry and Cork at the time, especially as it was at the beginning of the ‘Parish Carnival’ era. The flapper meetings were organised locally, outside the jurisdiction of any governing athletics bodies, and offered good cash prizes – he could win up to £2 (€2.54) at a big event at a time when a farm-labourer might earn around £4 (€5.08) per week. Prizes were given at sports meetings and he sold these for cash. He also competed in football and boxing – he received permanent hearing damage in a fight with a heavyweight.

Between 1954 and 1956, Murphy began travelling from home on a common bike for weeks on end, competing at sports and flapper meetings, sleeping in hay-barns and supplementing his winnings by performing his circus acts on the streets of towns and villages. He liked performing as a form of expression – walking up a ladder on his hands and fire-eating were his specialities.

His training techniques continued to develop and he began a number of correspondence courses on training methods. He continued to receive training information from abroad through his circus contacts, mostly from Russia, and he developed a strong interest in diet. He became an advocate of raw food and ate uncooked cereals, eggs, vegetables, cow’s blood and meat – there are tales of him in Cahirciveen, cycling away from the butcher’s shop, eating the steak as he went. He bought mail-order herbal remedies for ailments and injuries.

Murphy was given a 100-yard handicap in a mile running-race in Sneem in 1956 and he didn’t win any prize as a result. Seeing an end to his income from running, he turned to cycling. He was very successful at common-bike grass-track racing throughout Kerry in 1956 and was becoming renowned for the huge distances he was cycling to events. It was quite common for him to ride 60 miles (96 Km) to a meeting, compete, and ride home again on the same day.

Motivated by the sight of the exotic “Tralee boys” riding to track meetings in Caherciveen, carrying their light-weight track-bikes across their shoulders, as well as the relatively new Rás that he saw going thorough South Kerry, he made the decision to become “a proper cyclist” at the end of the 1956 season. He believed that he had the right recipe – the most advanced international training methods and dietary information available, as well as complete confidence in his own ability. The only missing ingredient was a proper road-racing bike, but he began a winter training regime on his common bike – 50 miles (80 Km) on week-nights, usually to Milltown and back, with up to 100 miles (160 Km) on Sundays, over circuits that included most of the big climbs in the Kerry mountains. He trained a lot at night, partly because he developed a peculiarity of being very secretive, but also because daylight was largely reserved for working. He continued to work wherever he could, mainly labouring in the bogs, quarries, roads and farms of the region, and he developed a reputation for stooking enormous amounts of turf.

His 1957 season went well. Murphy’s first proper road race was the 25-mile Time Trial Championship of Kerry in ’57 on a borrowed racing bike. He took a wrong turning and came last. He bought his first road bike at a track meeting in Currow for £10 (€12.70) – a ‘Viking’ in poor condition that Johnny Switzer from Tralee used in the 1955 Rás. His first road win was the 50-mile championship of Kerry, a victory that he attributed to the fact that he risked spending 16 shillings (€1) – the equivalent of a day’s wage for a labourer – on a hotel room rather than riding to the race that morning.

The winter of ’57/’58 was a difficult and decisive time for Murphy. He wanted to concentrate on cycling and win the 1958 Rás Tailteann, and continued his gruelling training schedule – he ate his Christmas dinner out of his pocket at the top of the Healy Pass, 60 miles (103 Km) from home. However, the conflict between his cycling ambitions and the drudgery and toil of his work caused him to become unsettled. This, combined with his unorthodox lifestyle and single-minded attitudes, led to increasing tension at home to the point where he eventually had to leave.

In the tradition of the spailpíns, the land-less peasants from the south-western seaboard who had attended the hiring-fares of Castleisland and Newcastlewest and went into ‘service’ in the rich farmlands of East Limerick and North Cork, Murphy looked towards Cork for work and shelter.

Banteer was his preferred destination, even thought it was in the neighbouring county and a world away from the south Kerry of the 1950s. He had encountered Banteer in sporting folklore and in his reading, and he thought that it must have been the centre of the sporting world – a place where his aspirations would be respected and supported. It had the best cinder cycling track in Ireland and was associated with sporting heroes such as Olympic gold medal winners, Dr. Pat O’Callaghan and Denis Horgan. It was also the home of the mock-heroic athletic champion, satirised in the ballad, ‘The Bould Thady Quill’.

On Easter Saturday, 1958, Murphy packed his only belongings into an old grain sack, mounted his bike, traversed the Iveragh Peninsula via the passes of Ballaghisheen and Beallaghbeama, and rode into Kenmare. He carried on through Killgarvan and Barradubh, and eventually arrived in Banteer. Somewhat disappointed, he found a small, typical Irish village, but walked into the local shop and announced his arrival and intention – “I’m a cyclist, where’s the track?”

The banked, cinder track in Banteer, north Cork. It was one of Ireland’s most advanced tracks at the time when track racing was the main form of competitive cycling. A five-mile race is in progress. Mick Murphy came to Banteer to prepare for the 1958 Rás

The Blackwater valley was indeed new world to him, with its lush landscape, modern farming methods, unionised farm labour with work ending at 6 p.m., and farmers who treated workers well. Most of all he found the place peaceful. He quickly found farm-work and based his training on Nadd Mountain, thus giving rise to the curiosity of the locals. Much of his riding was again done at night. He was desperate for the use of a gym, the cornerstone of his training, and set about preparing one. He selected a secluded spot in a wooded area near Mallow racecourse. From a neighbouring farm, he took two ‘half-hundredweights’ – 56lb. (25 kilos) iron weights that were commonly used on weighing scales at the time, and he took two similar 28lb. (12.6 kilos) weights from a shop in the village. He used socks filled with sand for the smaller weights. Believing in the qualities of goats’ milk because of the variety of herbs they ate, he took a goat from near Kilgarvin and brought it to his lair in a sling made of sacks. He also installed some hay as temporary bedding. From this base, he launched his assault on the 1958 Rás.

Early in the summer of 1958, Murphy suffered a serious loss of form that shattered his self-confidence and deeply upset him. He had left home and structured his life around his preparations and had publicised himself to a certain extent. He now had poor form at track-meetings and felt that he was being ridiculed. Racked with self-doubt, he decided that he couldn’t combine adequate training and rest with the regime of a farm labourer. He gave up his job, retreated to his woodland lair to rest and concentrated on his training on Nadd mountain.

Murphy performed his circus tricks in Cork city to pay for the enormous quantities of food that he was eating – he was especially consuming huge quantities of milk which he also put in his water-bottles, mixed at various times with raw eggs, honey, glucose, cow’s blood and a juice that he extracted from the stems of nettles. He bought pasteurised milk in shops, as he was cautious about a tuberculosis scare at the time.

One of the typical legends about Murphy – recounting how he cycled the Rás route before the event, but in the reverse way – probably comes from an episode of this time. Rumour reached him that he was not going to be chosen for the Kerry team because of his loss of form. He became desperate for money to enable him to get into the Rás, perhaps by going individually or by buying into another team. He also needed funds to subsidise him while he trained. He decided to turn to his circus contacts to borrow money that he might later work off. He cycled as far as Galway, looking for the circus, but when he learned that it was probably in Donegal he decided to return home. He made the return journey via Kildare, a jaunt that took him four or five days in all. Cyclists, with their usual network of contacts and their suspicions about rivals’ training, received reports of various sightings and the story grew that he was going around the Rás route in reverse direction.

From his woodland lair, Murphy trained, performed his acts and worked part-time with various farmers around the Banteer region in the run-up to the Rás. His form returned, and his win in the longest stage of Rás Mumhan ensured his place on the Kerry Rás team. His final two-week preparation took place while in an F.C.A. training camp at Kilworth, near Mitchelstown. He would finish at 4 p.m., train for three to four hours, sleep for a few hours in his den, train again during the night, rest again and ride back to camp to report for 9 a. m.

On the Friday morning before the Rás, he left his lair and the Blackwater valley for the last time and rode to Harding’s bike shop in Cork to get a few bits and pieces for his machine. He then started the 70-mile (112 Km) ride to Castleisland where he was to be picked up on Saturday, the day before the race. As he expressed it himself, “all the years of hardship and training had created an animal that the Rás wouldn’t be able to tame.”

A detailed investigation of the 1958 Rás confirms that much of what was written in the newspapers of the time, and the folklore that subsequently developed, was indeed exaggerated. Nevertheless, it all originated in actual fact and the scale of the embellishment is an indicator of the remarkable nature of the real events. Gene Mangan was one of the favourites but he was heavily marked on the first 100-mile (160 Km) stage from Dublin to Wexford, especially by the Dublin team. It was Kerry’s eighteen-year-old Dan Ahern and the unknown Murphy that got away, both in their first Rás, and Ahern won the stage. Murphy is reportedly to have had his first crash on this stage, about 2 miles outside Wexford – he clipped a bridge and his shorts were torn, but he came in second.

Monday’s second 120-mile stage (192 Km), from Wexford to Kilkenny, was where Murphy’s riding prowess was nationally seen for the first time. He was reported to have simply ridden away from the bunch and “strolled” into Kilkenny on his own. However, the events of the stage demonstrated not only Murphy’s strength, but also his single-mindedness and disregard for established etiquette and team strategy. Murphy powered away from the bunch after Carrick-on-Suir, leaving his team-mate, in the yellow jersey, behind. Ben KcKenna of Meath went with him, followed by Gene Mangan, also of Kerry. Two strong Kerry riders had now abandoned the yellow jersey to his fate in the bunch. Murphy simply rode McKenna off and had a three-minute lead at the Glenbower K.O.H. He arrived at the finish on his own, followed by McKenna at 58 seconds, with Mangan third. The unknown rider was now in yellow, after a performance that left the Rás astonished.

Murphy rode away from the stage finish at Kilkenny and disappeared for a while. This occurred a number of times during the Rás and led to another part of the Murphy legend – that he did 30-mile (48 Km) training spins after the stages. Murphy had in fact become dependent on his weight training and diet, and he rode out into the countryside, with his newly-won yellow jersey on his back, until he found a stone wall. He then did his weight training with suitably sized stones in a field for an hour. Afterwards, he went to a docile cow and, using a small pen-knife that he carried in his sock, bled a vein in the cow’s neck into his water-bottle and drank the blood. Murphy had read the African warriors had drank cow’s blood for a thousand years and he did it regularly. Also, there was a tradition in parts of Kerry of bleeding cows in times of want, especially on Sundays, leading to the expression that “Kerry cows know Sunday”. In all, Murphy performed his “transfusion” three times during the Rás.

The third 120-mile (192 Km) stage from Kilkenny to Clonakilty gave rise to one of the more remarkable events in the history of the Rás, from which the Murphy legend really began. He had wanted to lead the race going through Cork city and had the field strung out behind him on the climb at Watergrasshill. His freewheel mechanism failed on the run down into Glanmire, however, and he had to dismount when he rolled to a stop. The bunch passed and he saw the “Dublin boys massing to the front” as they assessed the situation. With no sign of his team car, Murphy watched the race disappear up the road and saw the end of his Rás hopes.

While he was standing in despair, with the race gone, two cows emerged from a gap up the road, followed by a farmer casually rolling the bike with his left hand on the handlebar. In the words of one report at the time, “instincts dictated reaction” – without consciously thinking he sprinted, jumped, landed cleanly on the bike and was gone even before the farmer realised what was happening. The bike was too big for him and under-geared, but he happily set out on the chase.

Murphy didn’t catch the bunch on the common bike as was reported, and the length of the chase was relatively short – probably between five and ten miles, but enough time was saved to keep him in contention.. It isn’t clear why he got no assistance from his team, but the team car had been at the rear of the race, attending to Gene Mangan who was having one of the most torrid days of this career – he was in danger of dropping out of the race as a result of a crash, two punctures and illness. He finished second-last on the stage, half-an-hour down, and fell from third to thirtieth place. Such was his condition that the NCA Chairman, Jim Killean, came to him that night and requested him to abandon the following day if he was not going well – he didn’t want Mangan to cross into his native Kerry in the state that he had been in that day.

The team car eventually came up and met with a bewildered farmer holding Murphy’s bike. They retrieved it, went up to Murphy and gave him the spare bike. He went through Cork city, again on his own and fearing that he would get lost, and chased into West Cork. He caught sight of the car cavalcade on the outskirts of Clonakilty, after 40 miles (64 Km) of chasing, and closed with the bunch just at the finish. He lost no time on the stage.

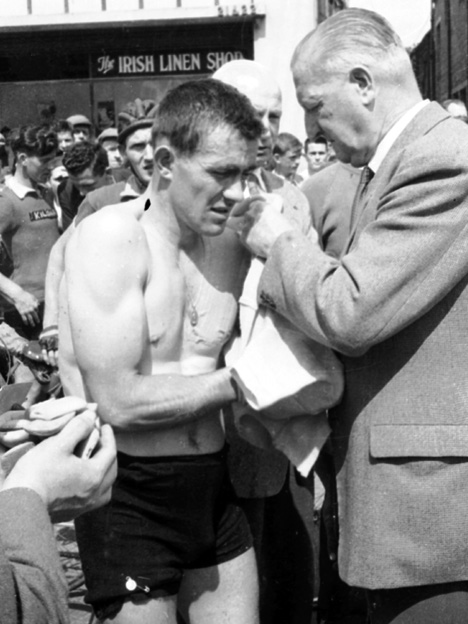

Mick Murphy in the yellow jersey at the finish of stage 3 in Clonakilty in Co. Cork, 1958. He is on the team’s spare bike, which replaced the common bike that he hijacked near Watergrasshill. It is a ‘Mercian’ bike that Gene Mangan borrowed for the event as a spare for the team. The ‘Cyclo Benelux’ front gear changer can be seen on the seat-tube, underneath the saddle. It was operated by leaning down and twisting it. The standard gearing was 46-48 front rings with a 14-16-18-20-23 rear block. Its 27-inch tyres gave a slightly higher gearing than modern 700 cm. tyres. It weighed 25 lbs. (11.25 kilos) and had ‘Michelin 25’ high-pressure clincher tyres.

The fourth 115-mile (184 Km) stage from Clonakilty to Tralee was to be even more dramatic. Murphy had been anticipating the Kerry mountains with relish – he admired the great Charly Gaul of Luxembourg who won the Tour de France the same year and he coveted the King of the Hills (K.O.H.) prize as much as the yellow jersey. He was away with a group of about ten, which included Mangan, and was in his element in his familiar mountains, in wet, squally weather, when he struck a bridge on a downhill bend near Glengariff. He crashed heavily on his left shoulder and hip, and damaged his bike. Mangan gave him his bike without hesitation, a situation reminiscent of Paddy O’Callaghan giving his bike to Mangan on Moll’s Gap in 1955 – an act that was important in Mangan’s eventual victory.

Murphy lost little time and caught the bunch on the climb to Turner’s Rock on the ‘Tunnel Road’. It took some time before the effects of the adrenaline from the crash wore off and pain took over – he first realised that he was in serious trouble crossing the bridge into Kenmare. Séamus Devlin of Tyrone tried to get away on Moll’s Gap but Murphy contained the attack. The Dublin team launching further attacks before Killarney. Devlin eventually escaped. Meanwhile, Gene Mangan, who had lost five minutes waiting for the car to come up with the spare bike, was having one of his great rides. He left the bunch on the climb out of Glengariff and got across to the leaders outside Killarney, making up the five minutes that he had lost at the side of the road. Devlin went on to win but Mangan’s presence steadied the situation in the leading bunch.

Large crowds had come from all over Kerry to see the stage-end as Murphy’s ride had now become national news. They saw Mangan narrowly beaten into third place – an indication that his form was returning and of what was to come – but Murphy’s arrival, in eight place, resulted in high drama – he was torn and bleeding, cycling with one hand and in obvious pain with a suspected broken collarbone. The town was rife with excitement and speculation as to whether he could continue or not, and if he could last the 111 miles (178 Km) to Nenagh the following day. Mangan’s generosity was given lavish praise and he, in turn, described Murphy as “an iron man” – a name that was to stick. Murphy was taken to hospital and reports of his injury varied from a dislocated shoulder, to a broken shoulder, to a bruised shoulder with torn ligaments.

Mick Murphy having difficulty in putting on the Yellow Jersey in Tralee at the beginning of stage 4. His upper-body strength – unusual for a cyclist – is clearly evident. His legs were comparatively small. His holy medal is temporarily pinned to his shorts, which are torn. The Jersey is being presented by Dr. Eamon O’Sullivan who came from an old republican and sporting family, was trainer of the Kerry football team and head of the NACA in Kerry. As such, he typified the nationalist-based sporting and political network that the sustained the Rás in its early years.

Murphy was reticent and did not encourage inquiry, making a judgement of his true condition difficult. He was in obvious distress at the start of the fourth stage, however, and had difficulty in putting on the yellow jersey. When pressed on the detail of Murphy’s condition at the start of that stage, one team member – Eddie Lacey – over forty years later, illustrated Murphy’s condition simply and descriptively: “they helped him onto his bike, they put his hands on the bars, they strapped in his feet, they held him up until the start, and then they pushed him off.”

The fourth stage was a bad day for Murphy. He floated at the back of the bunch and dropped off occasionally. Gene Mangan and Dan Ahern helped his as much as they could. They got brandy for him from the car which he drank, mixed with tea. He felt better after this. Ben McKenna attacked between Limerick and Nenagh and gained over a minute. Mangan went with him to mark him and won the sprint so easily from McKenna and Paddy Flanagan that the judges gave him five seconds. It was the first of his four consecutive stage wins. The main bunch came in a little over a minute afterwards with Murphy seventh from the front. He vomited at the finish but he had again saved the yellow jersey. In the early years of the Rás, the race leader was given a minute’s bonus for each day he held the yellow jersey and this helped to increase his margin daily.

Obvious anxiety as Mick Murphy is supported at the start of stage 4 of the 1958 Rás by the Kerry Manager, Liam Brick, (on right) and Micheál Ó Loingshgh, chairman of the Tralee stage-end committee: “they helped him onto his bike, they put his hands on the bars, they strapped in his feet, they held him up until the start, and then they pushed him off.”

Murphy was recovering. On Friday’s 6th stage – 120 miles (192 Km) from Nenagh to Castlebar – he left the main bunch shortly before the finish to gain 10 seconds. Mangan again won with 45 yards to spare over Eamon Ryan of Kildare. The pattern of the race continued again on the second-last 100-mile (160 Km) stage from Castlebar to Sligo. Murphy rode away from the bunch and had a minute advantage when he crashed near Castlerea. Again, he was without support. He stood up but fell forward onto his bike. This worried him as he had been told in his boxing days never to get up if he fell forward as it was considered a sign of concussion. He probably was concussed, because when he re-mounted, having straightening his handlebars, he rode the wrong way. The chasing riders were startled when they met the yellow jersey coming towards them and they pointed the other way to Murphy and shouted at him. Still confused, and suspecting some kind of trick, he rode on, but the next group of riders persuaded him to turn around. He got the knock later for want of food, and felt that his lead was seriously under threat. Eventually, he got food, survived, and arrived with the main bunch into Sligo.

At the end of the sixth stage into Castlebar. Eamon Ryan of Kildare (left) was second. Cathal O’Reily (centre) of Dublin was third on the stage and finished third overall. He was also leader of the victorious Dublin team. It was the second of Gene Mangan’s (right) four consecutive stage wins – a feat that was never to be repeated in the Rás and was even more remarkable considering that stage wins were a secondary consideration to protecting Mick Murphy’s lead. In a performance that the Irish Times called ‘remarkable’, Murphy left the main bunch towards the end of this stage and finished fifth.

Though he was reported to have numbness in his hands and having difficulty controlling his bike at times, Murphy took the final 140-mile (224 Km) stage from Sligo to Dublin by the scruff of the neck, although having a lead of 3 min. 54 secs. He again rode away from the bunch shortly after Sligo, followed by two Meath men – Ben McKenna and Willie Heasley. Mangan came up them after another epic chase – he had left the chasing group when it was five minutes down in Mullingar, 50 miles (80 Km) from the finish, and caught the leading group over 35 miles (56 Km). It was two Kerrymen verses two Meathmen, heading for the finish in Dublin, and both Kerrymen were convinced that they could win the stage. They exchanged words on the matter on the road. Mangan took his fourth consecutive stage and Murphy won the Rás by 4 minutes and 44 seconds.

The 1958 Rás was seen as a continuing triumph in Kerry, following the successes of 1955 and 1956, and the team was greeted with the usual civic reception in Tralee, followed by bonfire-lit tours to the home-towns of the team members. Disappointment at losing the team prize to arch-rivals, Dublin, was tempered by the compensation of new Rás records – Kerry held the jersey from start to finish, they had won six stages and Gene Mangan won four stages in a row – a feat that was never to be repeated in the Rás and that was even more remarkable considering that stage wins were a secondary consideration to protecting Murphy’s lead. But most of all, Kerry had produced the indestructible “Iron Man”, whose appearances now drew crowds all over the county.

Mick Murphy (on left) as a celebrity at a track meeting in Castleisland after his 1958 Rás win. He is on a ‘Claud Butler Olympic Sprint’ that Gene Mangan sold to Dan Ahern when he went to France in 1958. It has a ‘Major Taylor‘ all-steel adjustable handlebar stem. Jerome Dorgan of Blarney Cycling Club is on the right and his bike is being supported by Dan Ahern, who helped Murphy to his Rás win.

Mick Murphy (on left) as a celebrity at a track meeting in Castleisland after his 1958 Rás win. He is on a ‘Claud Butler Olympic Sprint’ that Gene Mangan sold to Dan Ahern when he went to France in 1958. It has a ‘Major Taylor‘ all-steel adjustable handlebar stem. Jerome Dorgan of Blarney Cycling Club is on the right and his bike is being supported by Dan Ahern, who helped Murphy to his Rás win.

Mick Murphy went back home to Caherciveen after the Rás and again survived on whatever labouring work he could find in the region. Contrary to myth, he was not a “one-Rás wonder” – he won two stages in the 1959 Rás and came third overall in 1960 as well as winning the K.O.H. category. Economic circumstances ended his cycling career. There were financial difficulties at home and he failed to get work on the drainage of the river Maine – one of a number of large schemes to provide employment as well as drainage in the ’50s and ’60s. He sold his gear, emigrated to the building sites in London in November, 1960, and never raced on a bike again. In all, he had competed on the road for just four years.

Mick Murphy was stoical, intelligent and creative, and an individualist and singular in every respect. He was also unique in physique for an elite cyclist – he was small in stature with massive upper-body strength, but with seemingly small and under-developed legs. He was described as “barrel-chested”, and had laughing, mischievous eyes. Liam Brick, the Kerry manager, in his descriptive and colloquial Kerry style, summarised Murphy thus – “he was small, sturdy, desperate strong, and he could pedal from morning ’til night.” He had great recuperative powers and the long stages of the era suited his style.

Murphy fancied himself as a climber and loved the mountains, but “strength” is the most often used description of him. His strength was indeed truly immense – his simple strategy was to jump to the front, turn on the power and wear off his opponents with grinding attrition. There are numerous examples of his riding away from groups of the very best of riders. Shay O’Hanlon, the most successful Rás rider ever, encountered Murphy as their careers briefly overlapped and he related one encounter with Murphy that left him “rattled”. This arose from a stage into Clonmel in the 1960 Rás Mumhan, where O’Hanlon, in yellow and with the help of two other very good riders, including Ronnie Williams from Dublin, tried to contain an attack from Murphy. Despite being at his very best, and having good help, he could not bring Murphy back an inch. His enormous effort left O’Hanlon stretched out on the street in Clonmel, totally exhausted and seriously questioning why he should punish his body to such extremes.

Yet, in spite of his accomplishment, Murphy had limitations as a racer. His tactical repertoire was limited and he was not generally admired as a stylish rider. He rode with a unique style – a fast cadence, interspersed with pauses, that was likened in appearance to that of a trotting pony. Dick Barry, who rode against him, observed:

“He had a way of pedalling the bike – he’d do ten strokes and then freewheel. He cracked up a lot of fellows the way he went – he wasn’t smooth at all – a very erratic rider and you couldn’t have a rhythm in a break with him.”

Neither could he ride close to a wheel and when he came back into a line he would leave a gap from the rider in front. This was both irritating and disconcerting for riders behind him, as they were always expecting a break to go from beyond the gap. It also meant that he seldom got shelter.

There were contrasts between Murphy and some of his team-mates, originating in background and outlook. He viewed himself as a total athlete in all respects, having the best professional preparation available, and had little tolerance or patience for the shortcomings of others. He didn’t fit comfortably into the discipline or etiquette of team racing and contributed little to team strategy or the needs of his team-mates. He would not ride to instructions that he disagreed with and was described colloquially as “headstrong”, or “impossible to manage”. He was reticent, shrewd, and had a suspicious nature, born out of his background – he could not trust that advice was for his benefit rather than for the selfish advantage of the giver. He kept to himself and nobody knew what he was planning or thinking. He considered that his team should have given him more support in 1958, with the exception of Mangan whom, he said, had “backed me to the hilt.” On the other hand, his team considered that he could not have won without its support, and that Dan Ahern, in particular, had been invaluable to him.

Certainly, Murphy was left unsupported at least three times as race leader in difficulty. But the absence of support illustrates the entirely different conditions that prevailed in the Rás in the ’50s. Kerry had one car to cover nine widely spaced out riders. With a strong emphasis on the county team placings, all the highly placed team members had to be supported. There was no radio or telephone communication, and no neutral service vehicles.

The Rás values ‘characters’ as much as gifted cyclists, and Murphy combined both in great measure. Cycling is a sport in which individualism thrives and Murphy’s idiosyncrasies therefore complemented his athletic ability to produce one of the great Rás men. Equally, the disparities between Murphy and his team-mates was not an issue in the Kerry Rás team of 1958. Still in its early years, there was euphoria surrounding the event, with an associated spirit of generosity and co-operation.

When the members of the great Kerry teams of the 1950s meet at the ceremonies that are held in their honour from time to time, discussion quickly and inevitably turns to Mick Murphy, the Iron Man, a shooting star that briefly but brilliantly flashed across the Irish sporting scene, illuminated the Rás, and faded just as quickly to leave one of the most enduring and enigmatic legends of the Rás.

With everything considered, Mick Murphy’s 1958 Rás win must rank as one of the truly epic feats of Irish sporting history.

Copyright © Tom Daly 2003

Note that sources of images are acknowledged in the original publication and that relevant copyright applies