A summary of my preparation for my first ultra race at age 65 and a brief description of the event

This article describes the preparation for my first ultra race which was undertaken at the age of 65 and raised some interest and queries.

Before the event I was asked to write about my preparation for my club in Killarney and, after I had finished the race, I received many inquiries which were difficult to answer adequately in casual conversation or by short text.

Therefore, I began this article as a brief outline of my preparation in order to fulfil both purposes and also to help others, particularly older riders, to understand that they too can undertake an event like this. However, as I got into the writing task it morphed somewhat to include some thoughts and observations on other aspects of the overall experience.

From the outset I wish to emphasise that this is not intended as a training model or ‘master plan’ for such an event, as each athlete’s attributes and life-circumstances are different and good preparation is always tailored to take these and the event’s demands into consideration.

Rachel Nolan, eventual winner of the long ‘Cúchulainn’ TransAtlantic Way 2020 route: 2,113Km with 25,225m of climbing in 5 days, 22hrs, and 20 min. Click here … to see a race report on Stickybottle.com.

What is The TransAtlantic Way?

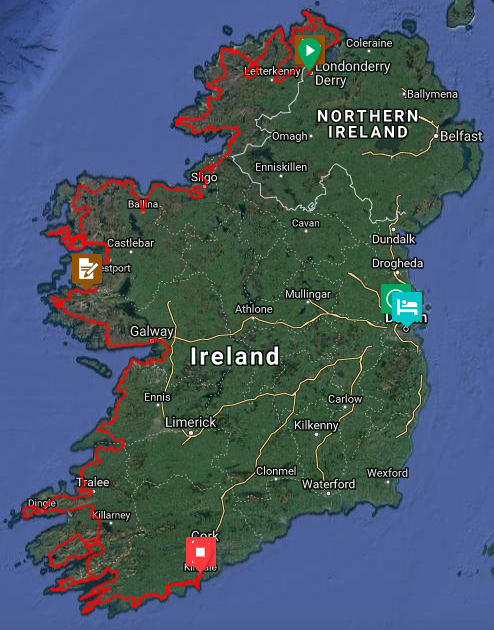

The 2020 TransAtlantic Way started in Derry/Londonderry and largely followed the Wild Atlantic Way to Kinsale. The long ‘Cúchulainn’ route was 2,113 Km with 25,225m of climbing and the shorter ‘Setanta’ route, which I did, was 1,540 Km long with 17,400m of climbing.

It is a self-supported event which means that the competitors are not allowed any outside assistance, have to carry all of their gear and do their own bike maintenance. There is just one stage – the clock doesn’t stop – and racers arrange their own bed or bivy whenever and wherever it suits them. The 2020 event was initially scheduled for June with up to 150 mainly-international riders signed on, but it was delayed until September because of Covid-19 restrictions and confined to Irish starters which numbered 12.

The short ‘Setanta’ TransAtlantic Way route: 1,540 Km long with 17,400m of climbing

Why?

The first question from many when hearing about my ambition to race this event was ‘why?’ And, even if not asked directly I knew they were thinking: “Why would you take up something like this at 65”?

This ‘why’ question is also useful in helping to set the scene for the preparation strategy because, as I stressed above, each plan must start with the uniqueness of the individual and his/her circumstances. Therefore, the following is a brief explanation of the ‘why’ so as to lay out the context of this particular case.

I stopped road-racing after the 2017 season because I had significant deterioration in my neck and spine and was told that I should try to avoid crashing, and so I focused on the National Masters Track Championships for September 2018 and won three national titles. A few weeks later I had two overdue surgical procedures in my shoulder and, just as I was recovering the following November, I suffered a bad disc problem in my spine that had me largely off my feet for three months and left me quite physically wasted.

I began training again in February 2019, from a rock-bottom base, with the aim of contesting just one title at the September Track Championships and did manage, I felt, to get in good enough condition to be competitive.

Then the event was cancelled at short notice and I said ‘never again’: I wouldn’t devote a season to an event that might not happen and began looking at a change in direction.

This was probably timely anyway as I had grown frustrated with the constraints of the rigid training programme for high-intensity racing: especially at my age and with my modest performance genes, there is very little leeway to deviate from a very structured programme and I was missing out on a lot of pleasurable cycling over the years.

I also had a longing to get back to the type of ‘adventuring’ that I did ‘back in the day’ and, being realistic, the time-window for doing ‘other stuff’ was closing at 65. It was time to move on and the The TransAtlantic Way ultra seemed to fit the bill.

Scoping the task

When I initially did an analysis of the project it seemed, frankly, quite impossible for me to do.

My main aim would be to finish but, being competitive by nature, I wouldn’t be happy to just ‘tour’ it and string it out to the cut-off date. While I had no ambitions to get ‘on the podium’ – survival was the main aim and there are no ‘Masters’ categories in ultra anyway – I would need to race it and ‘do a good time’. My race would, in effect, be a multi-day time-trial against myself.

For the performance I wanted I would need to average 250km per day, with 2,000-3,000 metres of climbing for six to seven days, carrying about 10% of my body-weight in extra kit, with very limited sleep or rest, in whatever weather the west coast and the mountains threw at me, while riding against the prevailing South Westerly winds. The event has had an annual failure rate of around 20%, most of whom, no doubt, were far younger and more robust than me.

Yes, an initial scoping of the task did confirm this to be ‘impossible’!

But, then again, others do this kind of event – it is their ‘thing’. For example, I rode with Mark Moroney from Derry for a little while in the 2019 event and he subsequently finished in a good time at age 69. He looked normal to me: yes, he probably had a much bigger engine and years of ultra-type experience but he was, basically, the same type of flesh and blood as me: If he could do it, why shouldn’t I?

In addition, I have a weakness for taking on big projects – biting off more than I should expect to chew – but then breaking the overall task down into innumerable items of detail and tackling each one, bite by small bite. Moreover, there was something irresistibly intriguing and challenging about the detail of this particular project: the training; equipment; race strategy; travel; and a whiff of unexplored territory and adventure.

It also coincided with my wish to take a different direction in my cycling and, so, I paid my deposit in October 2019 before I might get sense and change my mind: I had nine months to prepare for a June 2020 start.

Planning the training approach would begin with an analysis of my particular strengths and weaknesses, relative to the demands of the event. My strengths could have been summarized as follows – I had:

- Years of structured, consistent, good-quality training.

- Awareness of my own body, how near I could bring it to its limits and knowing when to step back from the edge.

- Good knowledge of the general principals of training which would need to be adapted to the specifics of the event.

- A keen sense of pacing which I knew would be vital to last the course: even a 500m TT on the track requires a good pacing strategy to do well.

- Excellent nutrition, courtesy of my wife, Ann.

- Time for training given that I was mostly retired.

While my weaknesses could be summarized as:

- Age: physiological decline varies and is complex but a typical 65-year-old can expect to have approximately 20-30% less capacity than at 35 and recovery is much slower.

- A range of age-related physical problems that included: a ‘dropped metatarsal head’ (a ball-of-the-foot problem); on-going issues with my shoulder and neck arising from surgery and the problems that led to it; significant arthritis and disc degeneration in my neck and lumbar spine; and arthritis in one knee.

- Lack of experience both physiologically and tactically with little ultra-long endurance training and no experience of doing a multi-day ultra event: rookies are very likely to make rookie mistakes no matter how well prepared.

Also, and while neither a weakness nor strength, I had just ‘average’ performance genes: when optimally trained, for example, my Aerobic Threshold is approximately 15% lower than leading riders of my age category – i.e. I was just ‘normal’.

‘Journey to a Start-Line is the name I gave to this short gallery of images taken during the January-September training period. I took very few pics during the race.

The Training Plan

It seems obvious that a high level of aerobic endurance should be paramount in my training approach but I reckoned that if I didn’t finish it would be something other than ‘the engine’ that would fail.

This was because the route is notoriously hard, especially the first 450km in Donegal which has 6,000 meters of climbing. Moreover, little of this is made up of the long steady mountains you might get on an Alpine holiday but, rather, those ‘WTF’ types of climbs and ramps that seem to rear up like a wall as you roll into them from a distance.

This is the nature of much of the route which is often described as ‘unrelenting’ and, given this in combination with the various age-related weaknesses summarized above, I had to give a high priority to developing what I refer to as ‘resilience and durability’.

In broadly outlining this, I will use a motoring equivalents of ‘the chassis’ (or frame), ‘the transmission’ and ‘the engine’, even though there is much overlap involved.

The chassis

This is the frame from which power is delivered and had to be durable so as to hold ‘form’ for very long hours, much of which would be on aero-bars, and also to absorb the stresses generated by steep climbing with a load. Given the deterioration of my lumbar spine which requires careful management at the best of times, along with neck and shoulder problems, it was imperative that this was strong and resilient.

I began supervised heavy lifting sessions in a gym in October and continued until January: with age there is less of an overall quota of energy to be expended in training and it is important to apportion this to different systems of the body as the priorities shift in emphasis through the course of the training programme. I continued with a conditioning regime at home until it tapered off gradually to a ‘maintenance’ level as the event approached.

The Transmission

This refers to the ligaments, tendons and joints through which power is transmitted to the pedals over extended time, and failure of one of these components is a common cause of abandonments.

The ‘chassis’ work summarized above contributed to this but it was also supplemented by on-bike strength work. This included over-geared, low cadence sessions such as big-geared standing-start ‘sprints’ on slopes, three-minute full-force efforts on drags at 50 rpm. in the time-trial position, and extended tempo efforts at around 60-70 rpm.

This type of work, in turn, contributed greatly to the core and ‘chassis’ strength as the trunk braces itself to withstand the one-sided stresses generated at low cadence with force.

The Engine

Building a big aerobic engine was clearly a big priority but I also had to pay attention to the other energy systems, broadly described as ‘threshold’ and Vo2Max’. It is good practice for older riders to keep stimulating these in order to minimize their decline with age and fitness and these higher levels also ‘raise the ceiling’ for aerobic endurance development.

The first stage of my aerobic strategy was to build one-day distances up to 300km. This also had a psychological purpose as I needed to develop a comprehension of these ‘crazy’ distances: to ‘get my head around it’ and believe they were possible, even for just one day.

After that 300km day I then planned to focus on back-to-back days, building up 2 x 300km. I reached this one-day target ride of 320 km on March 22nd and, five days later, the ‘stay at home phase’ of the Covid-19 restrictions were announced.

It was a time of great uncertainty for everyone, making planning difficult, and I reverted back to conditioning and stationary high-intensity work and developed these with on-bike work as the travel limits were gradually extended. This phase probably contributed quite a bit to the development of ‘resilience and durability’.

As the restrictions further eased I again began adding volume and back-to-back days as follows:

- 3 x 150km – mid May

- 3 x 175km – early June

- 3 x 200km – late June

- 2 x 250/300km – late July

- 2 x 300km – late July.

Making these multi-day rides ‘interesting’ was difficult with Covid travel restrictions but I made some circuitous routes for overnight visits to family. These were also useful for refining kit and tweaking position on the bike: you learn things after 12 hours on the bike that you don’t notice after six.

During some of these rides I also practiced avoiding ‘fiff-faffing’ which is the general expression used for spending unnecessary time stationary and which is a major cause of time loss on ultras. For example, I would time myself going into shops to grab a coffee and enough food for the next five hours on the road: 10 minutes was good enough, while 20 was poor.

The idea of building up to 2 x 300km days, when I only planned to do 250k days during the race, was partly psychological because I reckoned that if I could do consecutive 300km days then 250km ones would seem ‘easy’. While I might have ‘thought’ this, deep down I ‘knew’ that 300km on an un-loaded bike, with no steep climbing and in relatively good weather, would in fact be easy compared to doing 250km with a lot of very steep climbing, carrying 6-7 kg of kit, and possibly in wind and rain. Nevertheless, doing the final 2 x 300km was a big threshold to cross.

The higher-intensity sessions were reduced as more priority went to this aerobic endurance strategy: the last structured Vo2Max session was in late July and the last threshold session in early August. However, I kept the fitness of these energy systems topped up in an ‘enjoyable’ way with some time-trials, lively club rides and such like.

I also devoted key workouts to uninterrupted ‘sustained’ endurance work by avoiding routes with descents that would allow recovery. The longest mid-range aerobic endurance sustained ride was 6.5 hrs. and the longest sustained tempo ride was 3 hrs.

The final 2 x 300km days were part of a peaking period and, for those who are interested in training metrics, I had planned to peak at a ‘Chronic Training Load’ (CTL) of around 90. This is extremely high for my age and ability – the low 70s is consider normal for well-trained riders at this age (even though I have clients in this age-range who can hover in the 80-90s but they are the genetically gifted at national/international standard).

However, given that this would mostly be done at low intensities I reckoned on less potential for doing damage and, as I said previously, I had good experience of bringing my body to the edge and knowing when to step back.

I did reach 93.5 CTL on August 1st and held it thereabouts for three weeks. I was definitely sailing close to the wind during this period, but I got away with it and then settled into a long 2.5 week taper, but I won’t delve into its rationale or management here.

With that, I had reached my first goal of getting to the starting line. I still reckoned my chances of finishing to be 50-50 but, even if I didn’t, the journey up to this point was worth it as I had learned so much and had such new experiences.

In concluding this summary of my training I must again emphasize that this was for me and not intended as a model. Everybody is different: for example, stronger riders could carry the higher-intensity sessions further into the timescale; riders who don’t have the same time available would have to increase the overall load with more intensity; if I were to do another ulta, with the ‘memory’ of this one in my body, I might do fewer long back-to-back days and devote the energy to more speed-work; and so on.

The head game

Everything that I’d read about ultra emphasized the importance of the psychological aspect and, in truth, I didn’t pay much attention to this as I considered myself to be pretty resilient. Yes, I did scan a few articles on the subject but moved on: ‘Nothing new here’.

However, after chatting with one experienced ultra racer about preparation, and when he concluded with “I think you are underestimating the psychological aspect”, I did begin to wonder if there was something that I hadn’t fully envisaged. I will refer to this again below when discussing ‘how hard’ the event was.

The bike was a Trek Domane with a Sugino sub-compact chainset and aerobars. It weighed 16Kg loaded, without food or water.

All the other stuff

There were numerous other aspects to the preparation which readers may be curious about but which I am not dealing with in depth in this article, but this is a summary of the main ones:

- Bike setup: I used my regular road bike (Trek Domane) with a sub-compact chainset, aerobars and standard frame-bags for storage. It weighed 16kg fully loaded, without food or water.

- Clothing: this is personal to everyone, but I kept it to a bare minimum while still being cognisant of the scenario of getting a mechanical, late at night, on a bare mountain, in very bad weather, and out of phone coverage.

- Pacing: a pacing strategy, matching ability against the demands of the route, and avoiding ‘fiff-faffing’, is key to surviving the route on the one hand and getting a decent time on the other. I finished approximately six hours behind the schedule I had planned and the conditions would have accounted for that at least.

- Nutrition: food has to be sourced along the route and gastrointestinal distress can be a problem over time from the sheer volume, so riders have to learn what they can tolerate – thanks to Jill Mooney for her advice on this. Apart from having enough on the road, I ensured that I had 25gms protein in some form before I slept each night.

- Navigation, lights and power: again, these are personal choices which vary a lot from person-to-person. This is an area where I lost some time and nervous energy from making rookie mistakes.

- Night riding: this is off-putting initially but, as I was advised, feels safer than many busy daylight routes when done sensibly and riding through the dawn and dusk provided some of the most memorable riding experiences.

How did it go?

I didn’t intend to describe the event in any detail in this article but the following summary may be of general interest and also help to judge the effectiveness of the training approach.

When thinking ahead about the event the worst-case-scenario was that I would encounter rain and headwinds over the first few days in Donegal and, given its reputation, that my race could be over in just two days. These conditions were precisely what transpired: I got the first heavy shower on the way to the start and, once the race hit Malin Head after just 75km, we were facing very strong prevailing south-westerlies of 25-30kph and frequent rain for two days.

The wind in Donegal

At the end of the second day after 450km and 6,300m of climbing – much of it very steep and requiring a lot of effort in places just to keep the bike moving forward against headwinds – my legs were very tender and sore, particularly my quads, and the rain was also taking a toll. Moreover, I hadn’t slept well for the four hours I had allocated each night (even though the top racers usually ride straight through the first night or two or just take short bivy-naps).

Therefore, given the attrition to my legs especially, I reckoned my chances of finishing were somewhat below 50-50 at that point. Two of the 12 starters weren’t to make it out of Donegal and a further two – both leading contenders – abandoned soon afterwards.

The third day brought some respite with ‘only’ 2,000m of climbing and the wind down from ‘very strong’ to just ‘strong’ at 20kph, and I hit it head on for the first 120km west from Sligo towards Belmulett. Again, there was a lot of rain which was dispiriting at this stage but the conditions did add a particularly memorable flavour to the experience, especially on the steep, dramatic, swooping climbs and descents on Achill.

I had always reckoned that Day 4 would be a make-or-break day and I awoke to the alarm in Newport that morning feeling fresh and anxious to get going. I stood on the floor and everything seemed ok and, once I got on the bike and felt ‘good legs’, I believed for the first time that my chances went beyond 50-50.

It was also the first of just two days that were to be dry; Connemara was glorious and mostly deserted in the early morning; and I also passed the half-way point at the checkpoint at Killary Harbour.

Welcome food provided by the race organizer, Adrian O’Sullivan, at Checkpoint 2 at Killary Harbour at approximately half way

At this stage I was sometimes feeling a little smug as nothing ‘unexpected’ had happened: what I had read always warned to ‘expect the unexpected because the unexpected will happen’.

True to prediction, however, the first significant ‘unexpected’ occurred late on the fifth night in west-Clare when I crashed – a ‘momentary lapse of attention’ – and smacked my face against a stone wall. A selfie taken with the flash on my phone revealed that the damage was not as bad as it felt and I was delayed for only 10 minutes, but I did have to deal with a rather shocked and concerned guest-house owner in Lahinch when he was confronted by a somewhat old, bloody-faced cyclist.

My first real ‘feeling down’ period occurred on the first part of the fifth day, over 115km from Lahinch to Tralee. Crossing the Shannon into Kerry was a big milestone but it failed to lift my mood or my body and it was a time when I had to apply the often-quoted ultra-racing mantra of ‘just try to keep the bike moving forward’.

The body and the mood perked up later in the day and these swings in form are common in ultra. For example, on long training rides I had frequently experienced a period of boosted energy in the hours before dusk.

This was just as well as it was a hard slog against strong headwinds again during the 70 km from Tralee, over the Conor Pass to Dingle and onto Slea Head at dusk. The race organizer posted a video of Donnacha Cassidy, who eventually finished third, running a section of the Conor Pass that day as he couldn’t pedal the bike beyond 5kph against the wind.

Slea Head just before dusk on the longest day. The Blasket Islands – the most westerly point of Europe – are hidden in the mist.

That was my longest day at 270km which brought me to my home town of Killarney and I was nicely rewarded with support from my family and members of my cycling club who were out at the side of the road in the small hours of the morning.

I was in familiar mountain territory for the first part of the next day (Day 6), including the Gap of Dunloe, Moll’s Gap and the Healy Pass for starters. I had my second ‘unexpected’ late that evening in heavy mist and rain on the Sheep’s Head peninsula in south-Cork when my computer gave an unexpected low power warning. I went to charge it up but my power-bank was also dead and then, when I checked my phone to see how much power I had for back-up navigation and to find accommodation near that remote spot, that too was dead.

A video clip taken by race organizer, Adrian O’Sullivan, on the Healy Pass. I found the technical descent unusually difficult to judge and was ‘all over the road’. This made me aware that fatigue was begenning to effect my judgement and I slowed a lot on descents

It was both mystifying and concerning – my lights might not be far behind – but the mystery was solved when I went to charge everything up in a farmer’s shed and discovered that my charger was lying in an inch of rain-water at the bottom of my handle-bar bag and was also dead: it obviously had gotten damp and the charging must have failed during the previous night.

I lost a few hours but eventually got somewhat sorted and, later that night, I crossed paths in damp and heavy fog with both Donnacha Cassidy and Peter McColgan on an out-and-back section to Sheep’s Head. I had a brief chat with both: Cassidy was chasing McColgan for second place and he, in turn, was trying to keep ahead of Cassidy and also trying to catch the eventual winner, Rachel Nolan. Both of them intended to race straight through the night during which time Nolan was to crash twice in the push to stay ahead to Kinsale. I was heading for my customary four hours in a bed.

I went through another difficult phase the next morning and a painful saddle-sore wasn’t helping. Even the dawn, bringing clear skies and a slight tail-wind didn’t lift my spirits. That tail-wind even darkened my mood because, on the one day that I did get a prevailing tail-wind, it had moderated to what seemed a puny 10kph. It played with my head for a good while and I sulked about it like a child: ‘It’s just not fair’.

Again, however, my body and my mood lightened after I got back on the bike following a short break at Mizen Head and I really savoured the final 120km to the finish in Kinsale: a clear blue sky; the glories of the south-Cork coastline; a tail-wind which, however light, at least wasn’t a head-wind; a body that was undeniably very tired but still able to go at a reasonable speed with careful pacing; the prospect of meeting family and friends; time to mull over the adventures I’d had since signing up nine months previously; and what a wonderful blessing it was to be able to do it all.

It was the perfect run home and the finish was especially lovely and memorable with the welcome I received, and the sharing of the experience with family and friends.

Was the training approach effective?

The last 500m. to the finish at Kinsale is a steep climb that goes up to 10% and I had seen it the previous June when I rode the final section of the route on the first of 3 x 200km days, during which I stayed overnight with my grandchildren and their parents who live near Kinsale. On seeing it then I thought, “WTF: that’s just mean – to put a climb like that at the very finish”, and I skirted around it on the excuse that I was tired after 200km and still had two days’ riding ahead.

Now, after six days and nine hours, and 17,400m of climbing, I hardly noticed it – it was just a blip – and, not having to nurse my legs any longer, I enjoyed climbed it easily and casually out of the saddle.

So, yes: the training approach had worked. Rather than breaking me, the race had brought me ‘to the next level’ and, apart from a saddle-sore, I had no hint of any ailment or weak point that was likely to force a stop and I still had something left in my legs at the end.

While my ‘next level’ was still ‘entry level’, and I was nowhere near the standard of racers of my age range who are really good at this kind of thing, and possibly close to my limit had the race gone on for another day or two, I still drew special satisfaction from the ‘resilience and durability’ aspect of my preparation which had conditioned my body to withstand the course.

At the finish with my wife Ann (image courtesy of Bernadette Gallagher)

Was it hard?

This question brings to mind a quote from Emily Chappell in her book ‘Where There’s A Will: Hope, Grief and Endurance in a Cycle Race Across a Continent’:

“Throughout this race … I had listened to the other riders’ complaints about heat, wind, saddlesore and exhaustion with slight surprise. It was as if they hadn’t expected it to be difficult, or had believed that their meticulous preparations, their well-planned kit lists, their expensive gadgets and bike-fits, should have obviated any suffering they might experience during the race itself…”.

Similarly, many descriptions of ultra events descend into tedious, self-pitying tales of suffering along the lines of ‘every pedal stroke became an excruciating …..’, or introspective self-explorations about the meaning of life and ‘finding oneself’.

Perhaps I had just grown beyond all of that and long given up on the search to ‘find myself’, and when a sports reporter from the local Kerryman newspaper asked me if it was hard, I impatiently retorted: “It was a bike race – of course it was hard!”

But some – especially racers who haven’t experienced ultra – will still want to know: ‘How hard?’

The intriguing thing about ‘suffering’, as I pointed out in this article on ‘The World of Suffering’ in Cycling Weekly magazine, is that unlike most other aspects of training we have no metric to measure or accurately describe suffering. Therefore, all I can say is that both the training and the event were hard in a different way to the hardness of road and track racing.

This is perhaps best explained by the contrasting approaches that I took to mental strategies in both types of discipline. For road and track racing I had developed some effective mental strategies summarized in the article mentioned above: mainly ‘positive self-talk’ techniques which were aimed at overriding the brain’s impulse to slow down the body for self-preservation – to get beyond the pain.

The opposite was the purpose of similar self-talk strategies that I gradually evolved during the TransAtlantic Way. These were aimed more at calming the mind and controlling the impulse to fight the hills and the wind: to develop a kind of harmony between the prevailing conditions and the body as it went through its various fluctuations of fatigue and energy, moroseness and elation, and to focus the competitive instinct onto ‘the long game’ of pacing one’s way calmly to the finish.

I used two main mantras for this, the first being: ‘This Isn’t Hard’.

So, when questioning ‘why am I doing this’, the self-talk would go along the lines of: ‘This isn’t hard – you can climb off the bike any time you like’; ‘Going to work at a job you dislike every day is hard – this is not hard – being able to do this is a blessing’; ‘Giving up your life to look after an ill relative is hard – this is not hard – this is a privilege’.

The second evolved from a snippet of advice that I hooked onto, from Paul Birchall of Pi Cycles in Mallow who is an experienced ulta racer: “Remember to enjoy each hour as a nice time on your bike”, and that often had a soothing effect: ‘Savour this time and experience because it will never happen again’.

Referring back to ‘the head-game’ mentioned above, perhaps these strategies and mentality did help lessen the psychological demands of the event.

Therefore, in summary, , I didn’t find the training or the event ‘that hard’ compared to road and track racing: It didn’t have that same brutal physiological intensity and it was certainly more benign on my body and, though producing a lot of general fatigue, I didn’t have as much of that ‘beaten up’ feeling.

However, that comes with a caveat and the niggling question of ‘how hard was I really racing’? I could have saved fiff-faffing time from rookie mistakes with more experience but I don’t think I could have significantly increased my speed given the conditions. Nevertheless, had I been racing for a place on a podium, with a competitor just an hour in front or behind, perhaps it might have been a different experience and story.

And, as the event becomes more distant – a month at the time of writing – the competitive worm is hatching in my brain, seeding questions and doubts and perhaps demanding to be nourished: ‘How fast could you do it if you were really racing’?

Having fun with my daughter, Hannah, on the last 500m climb to the finish at Kinsale

To sum up

This article grew beyond my original intention of summarizing the training

approach but I hope it might be of help anyone considering an ultra by providing some insight, perspective and information.

I greatly enjoyed this event and drew a lot of satisfaction from the planning, training and competing. Dealing with the weather conditions probably made it more rewarding even though I didn’t appreciate this at the time.

The additional difficulties created by Covid-19, including less daylight and lower temperatures in September, along with less availability of food and

accommodation in certain parts, also contributed to making this a memorable edition of the race.

Reverting back briefly to the ‘why’ question: we are all seeking a different ‘hit’ from cycling in various ways and at different times in the cycle of our lives. This project did deliver for me in that sense, finding a ‘sweet spot’ which combining a new competitive challenge with a sense of travel, exploration and a little bit of adventure.

I would encourage any rider with an itch to try something different to give

this event a go and I will be happy chat with anyone seeking more information or perspective.

(Click here … for the TransAtlantic Way website)