“To retain as much muscle and bone density as possible from our mid-40s, we have to prioritise load-bearing, strength-type training”

In this second article of the ‘Going the Distance’ series for older riders, we examine the question of strength and conditioning. This may seem a surprising topic to begin with – why are we not talking about intervals, hours on the saddle, threshold power, and such like?

The Argument for Strength and Conditioning

In the first installment I emphasised the need to do things differently as we get older because of changes to our physiology and this is especially true in the case of muscle mass and bone density – beginning from the 40s, the ‘Use it Or Lose it’ saying couldn’t be more relevant. However, we also emphasised that some aspects of the ageing process can be significantly delayed by appropriate training and this equally applies to muscle and bone density.

We clearly want to minimise the loss of muscle given its role in performance and, apart from sport at all, it is important to maintain bone density. Even younger riders are at risk of low bone density and it is more relevant for women, especially after the menopause, in order to avoid osteopenia and osteoporosis.

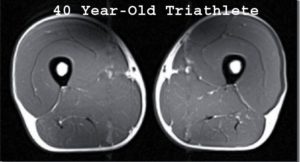

This argument for prioritising conditioning can be well illustrated by MRI scanning images from a classic study on muscle mass changes in older athletes by Wroblewski et al (2011).

The first image is a cross-section of an MRI scan of the thigh of a typical 40-year-old triathlete. You can see that he has good bone density in the centre, surrounded by a large muscle mass, and with little fat.

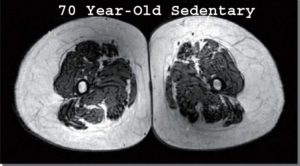

This is the thigh of a 70-year-old sedentary person. The differences from the 40-year old is obvious with a dramatic loss in bone density and muscle mass, and a very large increase in fat.

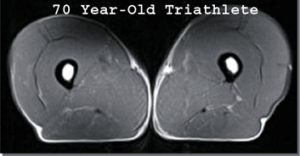

The third image is that of a 70-year-old triathlete. Two things stand out. First is the obvious positive difference from the sedentary person of the same age. However, perhaps most striking is the similarity to the first image of the 40-year-old triathlete.

Wroblewski’s study graphically burst the myth that muscle loss is primarily due to ‘natural’ ageing and, from the scientific standpoint, proved the ‘use it or lose it’ saying – the sedentary 70-year-old’s condition is more the result of inactivity than of ‘natural’ ageing.

Cyclists should keep in mind that the good bone density in these triathletes resulted from load-bearing in the running aspect of the sport, and we just don’t get this in most cycling activities. Another study (Medelli etc al, 2009) suggested that two-thirds of Masters cyclists could be classified as osteopenic – a precursor stage to osteoporosis – and that the spine was most at risk.

The key lesson is that, in order to retain as much muscle, bone density and related performance as possible from our mid-40s, we have to prioritise load-bearing, strength-type training.

Equally, it has many other benefits, including the stimulation of growth hormone and testosterone production, and slowing the decline of fast-twitch muscle fibers in proportion to slow-twitch. There is also good research evidence to show that much of back pain in cyclists is caused by weak core muscles.

Strength and Conditioning in the Training Programme

Apart from maintaining muscle and bone mass with age, conditioning is a sound basis for any cycling programme – a racing car with a powerful, finely tuned engine won’t perform to its optimum on a weak chassis.

However, here again the older rider may differ in the best approach to this. Some younger riders just don’t bother with it. Conventional training programmes which do include conditioning tend to begin including it in the off-season, taper towards the start of the season and cease during the racing period to avoid ‘dead legs’. So, there is somewhat of a ‘take it or leave it’ attitude and opinions differ.

But the game changes as riders become older. Remember, you’re losing it when you’re not using it and older riders should consider a year-round conditioning programme in some form. Space does not allow us to get into the details of a conditioning programme here, but these are some factors to consider if you take this advice on board:

- Don’t just go lifting weights randomly: a good coach, trainer or friend – knowledgeable about older cyclists – will assess your current strength levels based on your approximate 1MR (one max. repetition) and devise a suitable programme

- You can do damage to yourself with weights – you do need good advice and supervision, initially at least

- Your programme needs to ‘periodization’ just like the rest of your training – it will have different emphases and phases during the year and fit into your broader training programme: a coach can help to optimise this with a ‘maintenance’ phase during the height of the season that won’t take from performance

- Learning good technique with weights is vital, especially if you have knee or back problems. However, don’t be put off if you have chronic injuries or arthritis: conditioning can have very beneficial effects but you do need good advice

- If you have the option, free-weights are recommended more than machines: They work the ‘kinetic chain’ – the full multiple-joint range of muscle, tendons and joints in a similar sequence to cycling activities

- You can easily do your conditioning at home with a small amount of weights and equipment

- Self-restraint and self-monitoring is important – you must be able to discipline yourself and ditch the ‘no-pain-no-gain’ mentality

- Be cautious about the local ‘class’ of the techno-music, gut-busting variety

- While lower-body strength is most emphasised in cycling conditioning – with exercises like squats, lunges, step-ups and such like – incorporate at least some upper-body maintenance work

- Focus on form rather than effort – you have enough done when you can no longer hold perfect form

- Two or three sessions a week should be adequate for the average cyclist in the off-season, reducing to one maintenance session during the peak season

- Specialists, such as track sprinters, will obviously need an entirely different emphasis and specialist programme

- This type of work may result in the need for more stretching, rolling and myofascial release – there will be more about these in the Recovery installment of the series.

Core Strength and Conditioning

‘Core’ is currently fashionable but rather a vague expression. In cycling terms it can be understood as all the muscles which help maintain pelvic stability on the bike – this is the ‘core’ of power-production and needs to remain stable under load, sometimes over long periods.

Here is a simple exercise to test your core stability: after an hour or so on the bike, carefully float your hands just slightly off the brake-hoods and see how long your ‘core’ can maintain that position without the support of your hands. Be careful! And it is important not to alter your position to compensate. Riders with good core strength should be able to hold the position for 5 to 10 seconds at least.

Most of the pointers given above also apply to core conditioning, but here are some additional things to keep in mind:

- Form is even more important for core work – you shouldn’t be struggling or panting, and you are overloaded when you lose form

- Many local ‘classes’ are just old-fashioned ‘keep fit / aerobics’ classes re-branded to the more fashionable ‘core’ classes – try to get good instruction initially as form is important

- Many core activities emphasise abdominal exercises, but working the back – ‘the posterior chain’ – is even more important for cycling

- Good yoga and pilates exercises provide good core conditioning – the ‘warrior pose’ in yoga, for example, mimics the riding position closely

- Proper yoga and pilates also has a meditative and mindfulness element – this can provide a very good balance to the pressures of a training programme.

Strength and Conditioning on the Bike

Some strength and condition work can be done on the bike, but is not a complete alternative to off-the-bike work. The following are three types of session that can be done on the bike and focus on different aspects of strength and power.

Sustainable Strength Exercises

Pedal on a medium incline at around 60 rpm in a big gear for 5 to 15 minutes. These can easily be incorporated into a group spin on a rolling course. Form and technique are important and these drills are also good for improving your pedalling technique:

- Remain seated and remain aerobic

- Effort is moderate – perhaps 6 out of 10 – with most effect on the legs

- You shouldn’t have a death-grip on the bars, be rocking from side-to-side, or panting – keep the hands and upper body relaxed and still, with no movement above the saddle

- Focus completely on the foot-pedal interface, with power being evenly applied

- Concentrate on pulling right through the bottom of the stroke, and up again

- Keep doing some high-cadence work during the winter – you don’t want this kind pedalling to slow your normal cadence.

Sustained Power Exercises

Begin by rolling at moderate speed in a big gear on the flat or slight incline, and then start ‘stomping’ on the pedals. These are stressful and will build lactate.

- Remaining seated

- Try to get the bike up to speed as much as possible – basically a sprint from a low speed in a very high gear

- Sustain the effort for just 15 to 20 seconds

- Recover fully between each effort and four or five efforts are usually enough.

Peak Power Exercises

Begin at almost a dead stop on a steep hill, in one of your biggest gears. Then, make a full, out-of-the-saddle effort. Note:

- These are demanding and deserve caution – they mimic the squat in the gym but there are more things to go wrong on a bike

- Form is important: do not throw the bike around – the upper body should remain as vertical as possible

- The effort should be short – no more than ten pedal strokes each side

- This is very stressful on the back and you should be built up with care, but it is less so on the knees because the knee angle is more open out of the saddle, reducing patellar stress.

Like all training, this type of conditioning on the bike can be mixed-and-matched in various ways and incorporated into the annual training plan. Here are some pointers to keep in mind if you decide to do this kind of work:

- As with all intervals, these should be periodized and begin at a manageable level to avoid injury

- Depending on the intensity, these can be stressful on the knees and lower back – thoroughly warm up, build up the intensity gradually, and cut back if soreness occurs

- They can’t be done properly on an indoor trainer – the dynamics involved are different as the trainer absorbs much of lateral stresses normally controlled by the core in hard efforts

- Your bike needs to be in top condition – you could have a nasty outcome if a chain or other component failed during some of these exercises, particular the Peak Power intervals

- As with all intervals, you are finished when your output drops below 5 to 10 percent of the normal – then it’s time to flick into a low gear and enjoy the cruise home.

What Next?

The information and advice given in this review of strength and conditioning may appear daunting if it isn’t already part of your routine – ‘How am I going to fit this in with everything else’?

However, the time and commitment involved is much less than the cycling aspect of the sport. You can get a lot done in half-an-hour, even though 45 minutes to an hour is more common. Some can fit it into the work day. It can also be done at home, and when it’s dark outside or the weather is bad. With good advice from a coach, trainer or knowledge friend, strength and conditioning can be incorporated into your programme without altering it significantly.

The most important thing, we hope, is that we have convinced you of the need to pay attention to it, and to prioritise it as you get older. Remember, if you in your mid-40s or beyond, you’re losing it if you’re are not using it, and it’s happening now.

- Part 3: Going Faster and Going Further – Training and Performance – available here …

- Back to ‘Introduction’ with menu of articles …. available here ….